The Shannon Weaver Model, a foundational concept in information theory, significantly impacts how we understand communication processes. This model, initially developed at Bell Laboratories, conceptualizes communication as a linear transmission, providing a framework for analyzing various communication breakdowns. The understanding of noise, as defined by the Shannon Weaver Model, allows practitioners to better analyze potential risks within these communication models and improve the quality and reduce the risk of failure in shannon weaver model communication.

Ever found yourself in a situation where your message was completely misinterpreted, leading to frustration or even conflict? We’ve all been there. Whether it’s a simple misunderstanding in a text message or a more significant communication breakdown at work, these experiences highlight the inherent complexities of conveying information effectively.

These daily experiences with miscommunication underscore a fundamental point: communication is rarely a straightforward process. It’s a delicate dance of encoding, transmitting, and decoding, with numerous opportunities for things to go awry.

Why Communication Models Matter

To navigate these complexities and gain a clearer understanding of what makes communication effective (or ineffective), we often turn to communication models. These models serve as simplified representations of the communication process, allowing us to analyze its various components and identify potential points of failure.

They provide a framework for understanding how messages are created, transmitted, received, and interpreted. This framework can be invaluable in identifying the source of communication problems and developing strategies for improvement.

The Shannon Weaver Model: A Foundational Framework

Among the many communication models developed over the years, the Shannon Weaver Model stands out as a foundational cornerstone. Conceived in the late 1940s, this model, sometimes referred to as the "mother of all models," provides a structured and linear framework for analyzing communication.

It emphasizes key elements like the sender, the channel through which the message travels, the ever-present possibility of noise disrupting the signal, and, of course, the receiver.

At its core, the Shannon Weaver Model offers a powerful lens through which we can examine communication breakdowns and strive for clarity. By understanding its components and how they interact, we can equip ourselves with the tools to communicate more effectively in all aspects of our lives.

Thesis Statement: The Shannon Weaver Model, a cornerstone of Communication Theory, offers a structured framework for analyzing communication, emphasizing key elements like sender, channel, noise, and receiver.

Ever found yourself in a situation where your message was completely misinterpreted, leading to frustration or even conflict? We’ve all been there. Whether it’s a simple misunderstanding in a text message or a more significant communication breakdown at work, these experiences highlight the inherent complexities of conveying information effectively.

These daily experiences with miscommunication underscore a fundamental point: communication is rarely a straightforward process. It’s a delicate dance of encoding, transmitting, and decoding, with numerous opportunities for things to go awry.

Why Communication Models Matter

To navigate these complexities and gain a clearer understanding of what makes communication effective (or ineffective), we often turn to communication models. These models serve as simplified representations of the communication process, allowing us to analyze its various components and identify potential points of failure.

They provide a framework for understanding how messages are created, transmitted, received, and interpreted. This framework can be invaluable in identifying the source of communication problems and developing strategies for improvement.

The Shannon Weaver Model: A Foundational Framework

Among the many communication models developed over the years, the Shannon Weaver Model stands out as a foundational cornerstone. Conceived in the late 1940s, this model, sometimes referred to as the "mother of all models," provides a structured and linear framework for analyzing communication.

It emphasizes key elements like the sender, the channel through which the message travels, the ever-present possibility of noise disrupting the signal, and, of course, the receiver.

At its core, the Shannon Weaver Model offers a powerful lens through which we can examine the communication process. But to truly appreciate its significance, it’s essential to understand the context in which it emerged and the brilliant minds behind its creation. Let’s delve into the historical backdrop and meet the architects of this influential model.

The Architects: Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

The Shannon Weaver Model, a cornerstone of communication theory, didn’t arise in a vacuum. It was a product of its time, deeply influenced by the historical context of the post-World War II era and the burgeoning field of information theory.

The Post-War Landscape and the Rise of Information Theory

The years following World War II witnessed a surge in technological advancements, particularly in the realm of communication. The need to transmit information efficiently and reliably became paramount, driving the development of new theories and technologies.

Information theory, a revolutionary field that quantifies information and explores its transmission, emerged as a critical area of study. This era provided fertile ground for the development of models like Shannon Weaver, which aimed to address the challenges of effective communication in an increasingly complex world.

Introducing Shannon and Weaver: The Masterminds Behind the Model

The Shannon Weaver Model is attributed to two brilliant individuals: Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver. Each brought a unique perspective and expertise to the table, resulting in a model that has stood the test of time.

Claude Shannon: The Father of Information Theory

Claude Shannon, often hailed as the "father of information theory," was a mathematician, electrical engineer, and cryptographer. His groundbreaking 1948 paper, "A Mathematical Theory of Communication," laid the foundation for the field and introduced many of the concepts that underpin the Shannon Weaver Model.

Shannon’s work provided a mathematical framework for understanding information, its measurement, and its reliable transmission across noisy channels. His insights into encoding, decoding, and noise reduction were revolutionary and continue to influence communication technologies today.

Warren Weaver: Bridging the Gap

Warren Weaver, a scientist and science administrator, played a crucial role in interpreting and popularizing Shannon’s work. Weaver recognized the broader implications of Shannon’s mathematical theory for communication in various fields, including human communication.

In his 1949 article, also titled "A Mathematical Theory of Communication," Weaver expanded upon Shannon’s ideas, making them more accessible to a wider audience and highlighting their relevance to disciplines beyond engineering.

He introduced the concept of three levels of communication problems: technical (accuracy of symbol transmission), semantic (interpretation of the message), and effectiveness (impact of the message on the receiver). This framework significantly broadened the scope of the model’s application.

Bell Labs: The Crucible of Innovation

The Shannon Weaver Model was developed at Bell Telephone Laboratories (Bell Labs), a renowned research and development institution that has been at the forefront of technological innovation for decades.

Bell Labs provided Shannon and Weaver with the resources and collaborative environment necessary to develop their groundbreaking ideas. The model emerged from the practical challenges of improving telephone communication, reflecting the lab’s commitment to solving real-world problems through rigorous scientific inquiry.

The legacy of Bell Labs continues to resonate in the field of communication, with many of its innovations shaping the way we communicate today.

Anatomy of Communication: Deconstructing the Shannon Weaver Model

At its core, the Shannon Weaver Model offers a powerful lens through which to dissect the communication process.

It allows us to examine each element individually and understand how they interact to facilitate (or hinder) the successful transmission of a message. Let’s break down each component.

The Elements of the Model: A Step-by-Step Guide

The Shannon Weaver Model is best understood by examining each of its components in sequence, tracing the journey of a message from its origin to its final destination.

Information Source: The Genesis of the Message

The process begins with the information source, the originator of the message.

This source is where the thought, idea, or data that needs to be communicated first takes shape.

It could be a person with something to say, a computer generating data, or even an event triggering a response. The quality and clarity of the information at this stage are crucial, as they set the foundation for all subsequent steps.

Sender: Crafting the Message

The sender is the individual or device that chooses and prepares the message for transmission.

The sender’s role is to take the raw information from the source and formulate it into a coherent message that can be understood by the intended receiver.

This involves selecting the appropriate language, tone, and format for the message.

Encoder: Translating the Message

The encoder transforms the message into a signal that can be transmitted across the chosen channel.

This process of encoding is essential for converting the message into a format suitable for the medium of communication.

For example, when speaking, our vocal cords and mouth act as the encoder, converting our thoughts into sound waves. In digital communication, a modem encodes digital data into analog signals for transmission over telephone lines.

Channel: The Conduit of Communication

The channel is the medium through which the encoded signal travels from the sender to the receiver.

This can take many forms, including airwaves for speech, telephone lines for phone calls, fiber optic cables for internet communication, or even a simple handwritten note.

The choice of channel significantly impacts the speed, reliability, and potential for interference in the communication process.

Noise: The Unwanted Intruder

Noise is any interference that distorts the signal during transmission, hindering accurate reception.

Noise can manifest in various forms, including physical noise (e.g., loud sounds disrupting a conversation), psychological noise (e.g., preconceived biases affecting interpretation), and semantic noise (e.g., misunderstandings arising from jargon or ambiguous language).

Minimizing noise is a key challenge in effective communication.

Decoder: Interpreting the Signal

The decoder reverses the encoding process, converting the signal back into a message that the receiver can understand.

This involves translating the received signal into a recognizable form, whether it’s converting sound waves back into spoken words or deciphering digital data.

Receiver: The Message Recipient

The receiver is the intended recipient of the message.

The receiver’s ability to accurately decode and understand the message depends on factors such as their knowledge, experience, and attention.

Destination: Reaching the Target

The destination is the ultimate point where the message is intended to reach.

This marks the end of the communication process, where the received message ideally has the desired impact on the receiver.

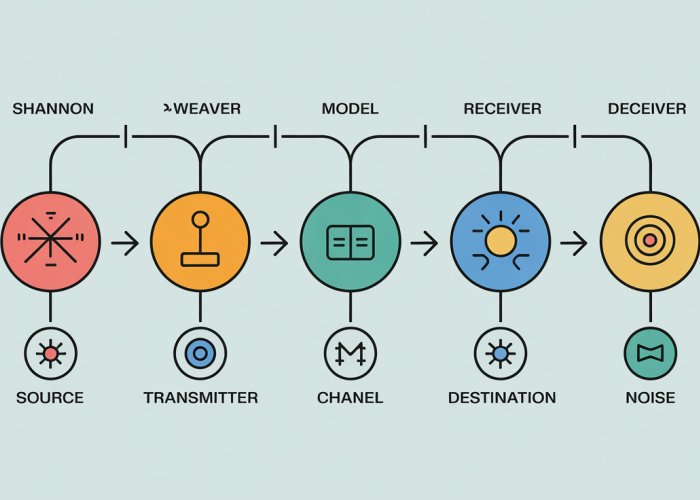

Visualizing the Model: A Diagrammatic Representation

To further clarify the relationships between these elements, consider the following diagram:

[Insert Diagram Here: A visual representation of the Shannon Weaver Model, with labeled components arranged in a linear sequence: Information Source -> Sender -> Encoder -> Channel -> Noise (affecting the channel) -> Decoder -> Receiver -> Destination]

This visual aid provides a clear illustration of the flow of information through the Shannon Weaver Model, emphasizing the linear progression from source to destination and the potential for noise to disrupt the process.

The Disruptor: Understanding the Impact of Noise

Having explored the intricate dance between sender, encoder, channel, and receiver, it’s time to address a critical element that can derail the entire communication process: noise. Noise, in the context of the Shannon Weaver Model, isn’t just limited to the static on a phone line or the rumble of a passing truck.

It encompasses a much broader range of interference that can distort or obscure the intended message, leading to misunderstandings and communication breakdowns. Understanding the various forms of noise and their impact is crucial for effective communication.

Defining Noise: More Than Just Static

In the Shannon Weaver Model, noise is defined as any factor that interferes with or distorts the signal as it travels from the sender to the receiver. This interference can take many forms, impacting the clarity and accuracy of the message. It is paramount to acknowledge these diverse sources of noise in order to develop mitigation strategies and facilitate robust communication.

The Three Faces of Noise: Physical, Psychological, and Semantic

Noise manifests in a variety of ways, broadly categorized into physical, psychological, and semantic forms:

-

Physical Noise: This is the most apparent type of noise, encompassing external environmental distractions that impede clear communication.

Examples include loud construction sounds during a meeting, poor audio quality on a video call, or illegible handwriting on a handwritten note. These tangible interferences directly affect the transmission and reception of the signal.

-

Psychological Noise: This form of noise arises from the internal mental states and biases of the communicators.

Preconceived notions, emotional baggage, personal beliefs, and assumptions can all cloud our judgment and distort the message we receive. For instance, if someone has a negative predisposition toward the speaker, they might misinterpret the speaker’s message, even if it’s perfectly clear.

-

Semantic Noise: This type of noise stems from misunderstandings of the symbols used in communication, primarily involving language.

It occurs when the sender and receiver have different interpretations of the words, phrases, or jargon employed in the message. Using technical jargon with a non-technical audience or employing slang that is not universally understood are prime examples of semantic noise.

Real-World Disruptions: Examples of Noise in Action

The impact of noise can be observed in countless real-world scenarios. Consider these examples:

- A Noisy Construction Site: A project manager attempts to explain a complex architectural design to construction workers amidst the cacophony of machinery and hammering. The physical noise makes it difficult for the workers to hear the instructions clearly, leading to potential errors and delays.

- A Politically Charged Debate: Two individuals with opposing political views engage in a heated debate. Psychological noise, in the form of pre-existing biases and emotional investment, makes it difficult for them to objectively listen to each other’s arguments. They are more likely to focus on finding flaws in the other’s reasoning than on understanding their perspective.

- A Cross-Cultural Business Negotiation: A business executive from the United States attempts to negotiate a deal with a counterpart from Japan. Semantic noise arises due to cultural differences in communication styles and business etiquette. The American executive’s direct and assertive approach may be perceived as rude and aggressive by the Japanese counterpart, hindering the negotiation process.

- A Classroom Setting: A student preoccupied with personal problems struggles to focus on the lesson being taught. Psychological noise, in the form of anxiety and intrusive thoughts, prevents the student from fully absorbing the information being presented. This affects learning outcomes and academic performance.

Eroding Fidelity: The Implications of Noise on Message Integrity

The presence of noise inevitably affects the fidelity of the message – its accuracy and faithfulness to the original intent. The greater the level of noise, the greater the distortion and the further the received message deviates from the intended one.

When noise is significant, it can lead to:

- Misunderstandings: The receiver misinterprets the message, leading to confusion and potentially incorrect actions.

- Inefficiency: Time and resources are wasted in clarifying misunderstandings and correcting errors.

- Conflict: Miscommunication can breed frustration and animosity, leading to interpersonal conflict.

- Damaged Relationships: Persistent miscommunication can erode trust and damage relationships, both personal and professional.

Minimizing noise and maximizing signal clarity are therefore critical to achieving effective communication and fostering positive relationships. Addressing the potential for noise at each stage of the communication process – from message formulation to channel selection to attentive listening – is key to ensuring that the intended message is accurately received and understood.

Having explored the multifaceted nature of noise and its potential to disrupt communication, it’s essential to understand the different levels at which communication can fail. Not all communication breakdowns are created equal; some stem from technical glitches, while others arise from misunderstandings or a failure to achieve the intended impact. These varying levels of problems require distinct approaches to identify and address.

Identifying the Problems: Levels of Communication Issues

Warren Weaver, in his elaboration of the Shannon Weaver Model, astutely identified three distinct levels at which communication problems can occur: technical, semantic, and effectiveness. These levels offer a nuanced framework for diagnosing communication breakdowns and developing targeted solutions. Understanding these levels allows us to move beyond simply recognizing that communication has failed and pinpoint why it has failed.

Technical Problems: Ensuring Accurate Transmission

The technical level of communication problems concerns the accuracy of symbol transmission. This is the most fundamental level, focusing on whether the intended signal is accurately sent and received. Technical problems arise when there is a distortion or loss of information during the transmission process.

Examples include:

-

A faulty internet connection causing a video call to freeze and become unintelligible.

-

A scratch on a vinyl record causing skips and distortions in the music.

-

A typographical error in an email that changes the meaning of a sentence.

These issues can be objectively measured and often addressed through technological solutions, such as improving signal strength, using better equipment, or implementing error-correction codes. Addressing technical problems is a prerequisite for effective communication at higher levels.

Semantic Problems: Decoding the Message

Semantic problems arise when the interpretation of the message is inaccurate. Even if the signal is transmitted perfectly (without technical issues), the receiver may not understand the sender’s intended meaning. This can occur due to:

-

Differences in language or vocabulary.

-

Cultural misunderstandings.

-

Ambiguity in the message itself.

For example:

-

Using jargon or technical terms that the audience doesn’t understand.

-

Employing idioms or figures of speech that are unfamiliar to the receiver.

-

Sending a written message which tone can be interpreted various ways that are not intended.

Addressing semantic problems requires careful consideration of the audience’s background, knowledge, and cultural context. Clarity, precision, and the use of plain language are crucial for minimizing semantic noise. Senders must anticipate potential misunderstandings and proactively address them.

Effectiveness Problems: Achieving the Desired Impact

The highest level of communication problems relates to effectiveness—whether the message achieves its intended impact on the receiver. Even if the message is transmitted accurately and understood correctly, it may not lead to the desired outcome. This can happen if:

-

The message is not persuasive.

-

The receiver is not receptive to the message.

-

The message is poorly timed or delivered.

For example:

-

An advertisement that is informative but fails to motivate consumers to purchase the product.

-

A public service announcement about the dangers of smoking that does not change people’s behavior.

-

A well-reasoned argument that doesn’t resonate with the audience’s values or beliefs.

Addressing effectiveness problems requires a deep understanding of the receiver’s motivations, needs, and attitudes. Persuasion, empathy, and strategic messaging are essential for achieving the desired impact. Understanding the audience and tailoring the message to their specific context are paramount.

Having explored the multifaceted nature of noise and its potential to disrupt communication, it’s essential to understand the different levels at which communication can fail. Not all communication breakdowns are created equal; some stem from technical glitches, while others arise from misunderstandings or a failure to achieve the intended impact. These varying levels of problems require distinct approaches to identify and address.

Weighing the Scales: Strengths and Limitations of the Model

The Shannon Weaver model, while groundbreaking, is not without its critics.

It’s crucial to acknowledge both its strengths and limitations to fully appreciate its place in communication theory and its applicability to modern communication challenges.

Acknowledging the Model’s Strengths

The Shannon Weaver model’s enduring appeal lies in its simplicity and clarity.

It offers a straightforward, linear framework for dissecting the communication process, making it easily accessible to both academics and practitioners.

This clear structure allows for easy identification of key elements.

Clear and Linear Framework

The model breaks down communication into distinct components, such as the sender, encoder, channel, noise, decoder, and receiver.

This allows for a systematic analysis of each stage.

Such a structured approach simplifies the identification of potential points of failure in the communication chain.

Highlighting the Importance of Noise

One of the model’s most significant contributions is its explicit recognition of noise as a critical factor in communication.

By acknowledging that external factors can distort or interfere with the message, the model prompts communicators to proactively address and mitigate potential sources of interference.

This emphasis on noise has had a lasting impact on the study and practice of communication.

Wide Range of Applicability

Despite its simplicity, the Shannon Weaver model remains surprisingly versatile across various communication contexts.

From interpersonal interactions to mass media, the model’s core principles can be applied to analyze and improve communication effectiveness.

This adaptability has contributed to its widespread adoption across diverse fields.

Recognizing the Model’s Limitations

While the Shannon Weaver model provides a valuable foundation for understanding communication, it’s important to acknowledge its shortcomings.

Critics often point to its linear nature and lack of emphasis on the complexities of human interaction.

Linear and Simplistic Approach

The model’s linear, one-way flow of information fails to capture the dynamic and interactive nature of most human communication.

It overlooks the role of feedback, shared understanding, and the constant negotiation of meaning that characterizes real-world communication scenarios.

This can oversimplify human interaction.

Lack of Emphasis on Feedback and Context

The Shannon Weaver model underemphasizes the importance of feedback from the receiver to the sender.

In human communication, feedback is crucial for confirming understanding, correcting misunderstandings, and adjusting the message to meet the receiver’s needs.

Additionally, the model often neglects the broader social, cultural, and relational context in which communication takes place.

Primarily Technical Focus

The model’s origins in engineering are evident in its focus on the technical aspects of communication, such as signal transmission and noise reduction.

While these elements are undoubtedly important, the model gives less attention to the psychological, social, and cultural factors that shape communication processes.

This can lead to a narrow understanding of human interaction.

Acknowledging the limitations of the Shannon Weaver model is essential for a comprehensive understanding. However, its true value lies in its widespread application across diverse fields.

Let’s explore how this theoretical framework translates into tangible improvements and strategies in the real world.

Beyond Theory: Real-World Applications of the Model

The Shannon Weaver model, while initially conceived within the realm of telecommunications, possesses a remarkable adaptability that extends far beyond its origins. Its core principles of encoding, transmission, noise, decoding, and reception provide a valuable lens through which to analyze and optimize communication processes in various domains. From ensuring clear phone calls to crafting persuasive marketing campaigns, the model’s influence is pervasive.

Telecommunications and Engineering: Optimizing Signal Transmission

At its heart, the Shannon Weaver model is inextricably linked to telecommunications and engineering. The model’s primary function is to ensure accurate and efficient signal transmission.

Engineers utilize its framework to identify and minimize noise within communication channels, whether those channels are physical cables, radio waves, or fiber optic networks. By understanding the potential sources of interference and implementing strategies to counteract them, engineers can optimize signal clarity and reliability.

This can involve using error-correcting codes to detect and fix errors introduced by noise. In essence, the model acts as a blueprint for designing robust communication systems that can withstand the challenges of real-world environments.

Education: Improving Instructional Design and Delivery

The principles of the Shannon Weaver model also find application in the field of education, where effective communication is paramount. Educators can leverage the model to enhance instructional design and delivery by focusing on each element of the communication process.

For example, a teacher acting as the "sender" must carefully encode their message (the lesson) using clear and concise language, appropriate visuals, and engaging delivery methods. The "channel" might be a lecture hall, a virtual classroom, or printed materials. Recognizing potential sources of "noise" – such as distractions, unclear explanations, or cultural differences – allows educators to proactively address these barriers.

By ensuring that the message is effectively decoded and received by the students, educators can maximize learning outcomes and create a more engaging and impactful learning experience. This might involve incorporating feedback mechanisms to gauge student understanding and adjust the delivery accordingly.

Marketing and Advertising: Crafting Effective Messages

The world of marketing and advertising is another fertile ground for applying the Shannon Weaver model. In this context, the model becomes a strategic tool for crafting compelling messages and selecting appropriate channels to reach the target audience.

Marketers act as "senders," carefully encoding their messages to resonate with the intended "receivers." The "channel" might be a television commercial, a social media ad, or a print advertisement. Understanding the potential sources of "noise," such as competitor advertising, consumer skepticism, or cultural sensitivities, is critical.

Effective marketing campaigns strive to minimize noise and maximize the likelihood that the message is accurately decoded and acted upon by the target audience. This often involves conducting thorough market research to understand the audience’s needs, values, and communication preferences. The goal is to create a message that cuts through the clutter and delivers the desired impact, whether it’s driving sales, building brand awareness, or changing consumer behavior.

Decoding Communication: Shannon Weaver Model FAQs

Here are some frequently asked questions about the Shannon Weaver model of communication, designed to help you better understand this foundational concept.

What are the key components of the Shannon Weaver model?

The Shannon Weaver model consists of five key elements: an information source, a transmitter, a channel, a receiver, and a destination. Additionally, it accounts for noise that can disrupt the communication process. Understanding these components is crucial for grasping how the model functions.

How does noise affect communication according to the Shannon Weaver model?

Noise, in the Shannon Weaver model, refers to any interference that disrupts the transmission of a message through the channel. This can be literal noise, or any other factor that distorts the signal and prevents accurate decoding by the receiver. The model emphasizes that noise is always a factor in communication, so it’s important to understand how it can affect the message.

Is the Shannon Weaver model a linear or circular model of communication?

The Shannon Weaver model is considered a linear model of communication. It focuses on a one-way flow of information from a source to a destination, without explicit feedback loops. While subsequent communication models incorporate feedback, the shannon weaver model lays the foundation for understanding the linear process.

What are some limitations of the Shannon Weaver model?

One of the main limitations of the Shannon Weaver model is its simplicity. It primarily focuses on technical aspects of communication and doesn’t fully account for contextual, social, or cultural factors that influence how a message is interpreted. Also, the model doesn’t deal with multiple sources of communication or other factors like relationship of the source and the receiver.

Hopefully, this breakdown of the Shannon Weaver Model helps you understand the nuts and bolts of communication a little better! It’s a classic for a reason. Now go out there and put the shannon weaver model into action in your own communications!