Memory, a cornerstone of human cognition, is surprisingly fallible, and understanding its nuances can dramatically improve our learning and retention capabilities. One such nuance is proactive interference example, a fascinating phenomenon studied extensively in cognitive psychology. Consider the brain, often likened to a complex computer; its processing capacity can be hampered when previously learned information disrupts the encoding of new information. Hermann Ebbinghaus, a pioneer in memory research, laid the groundwork for understanding these memory distortions, highlighting how earlier associations can interfere with the formation of new memories. A clear proactive interference example can be seen when individuals struggle to remember a new phone number, continually recalling their old one instead; this makes cognitive load higher, resulting in forgetting.

Ever found yourself calling your new colleague by your old coworker’s name? Or maybe you keep entering your old password on a website you updated last week?

It’s a frustrating experience, this feeling that your brain is betraying you.

You know the correct information, but somehow, the wrong information keeps popping up. This phenomenon, where old information butts in line and makes it difficult to recall new information, is called proactive interference.

It’s not just a minor annoyance.

Proactive interference can impact learning, memory, and overall cognitive performance in countless everyday scenarios.

Decoding the Frustration: What is Proactive Interference?

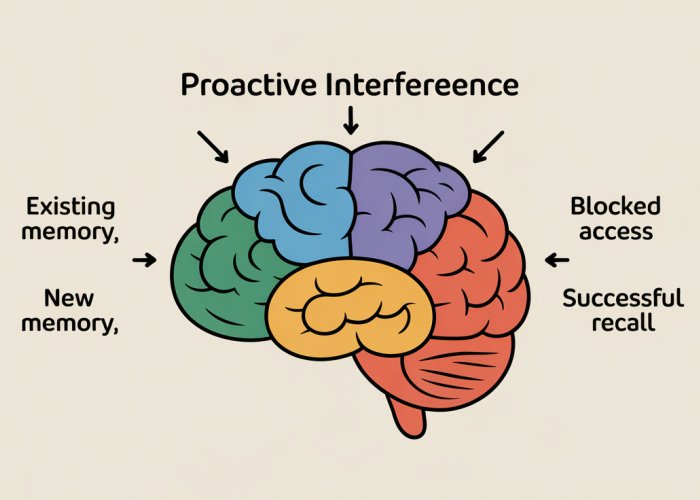

Proactive interference occurs when previously learned information interferes with your ability to learn or recall new information. Think of it as your old memories being a bit too enthusiastic, crowding the stage and preventing new memories from getting their chance to shine.

This isn’t just a quirk of the brain; it’s a fundamental aspect of how our memories work.

The Purpose of This Exploration

This article aims to be your guide to understanding this common, yet often overlooked, cognitive phenomenon.

We’ll delve into the nature of proactive interference.

We will illustrate it with relatable examples, differentiate it from other types of forgetting, and most importantly, offer practical strategies to minimize its impact on your life.

Consider this your toolkit for mastering your memory and reclaiming control over what you remember.

Ever found yourself calling your new colleague by your old coworker’s name? Or maybe you keep entering your old password on a website you updated last week?

It’s a frustrating experience, this feeling that your brain is betraying you.

You know the correct information, but somehow, the wrong information keeps popping up. This phenomenon, where old information butts in line and makes it difficult to recall new information, is called proactive interference.

It’s not just a minor annoyance.

Proactive interference can impact learning, memory, and overall cognitive performance in countless everyday scenarios.

This article aims to be your guide to understanding this common, yet often overlooked, cognitive phenomenon.

Consider this your toolkit for mastering your memory and reclaiming control over what you remember.

So, we have a basic grasp of what proactive interference is, but the natural next question is: how exactly does this "blocking" happen? Let’s dive deeper into the mechanics of memory and explore the subtle ways our past experiences can shape – and sometimes distort – our present recall.

Decoding Proactive Interference: How Old Memories Block New Ones

At its core, proactive interference describes a very specific type of memory failure. It’s not simply forgetting; it’s a case of your existing knowledge getting in the way of absorbing or retrieving new information.

Think of your mind as an overstuffed filing cabinet.

When you try to add a new file, the old ones can tumble out, creating a jumbled mess.

It becomes difficult to locate the new file because it’s buried beneath a pile of older, but similar, documents.

The Mechanism of Memory Interference

The interference doesn’t occur randomly; it’s driven by the way our brains encode and retrieve information.

When we learn something new, our brains create pathways and connections that represent that information.

However, if the new information is similar to something we already know, these pathways can overlap.

This overlap creates competition during retrieval.

When we try to recall the new information, the older, more established pathways can activate instead, leading to the "wrong" memory surfacing.

Essentially, the older memory has a head start and outcompetes the newer one.

The stronger the original memory and the more similar the new information is, the greater the interference will be.

Proactive Interference, Memory, and Learning: A Tangled Web

Proactive interference isn’t an isolated quirk; it’s intricately connected to the broader processes of memory and learning.

It highlights the fact that memory isn’t a perfect recording device.

Instead, it’s a reconstructive process that is constantly being shaped by our prior experiences.

In the context of learning, proactive interference demonstrates that prior knowledge can both help and hinder our ability to acquire new skills and information.

While existing knowledge can provide a foundation for new learning, it can also create roadblocks if the new material is similar to, but different from, what we already know.

This is particularly relevant in fields like education, where students constantly build upon existing knowledge.

Interference Theory: A Framework for Forgetting

To fully understand the role of proactive interference, it’s helpful to consider Interference Theory.

Interference theory proposes that forgetting occurs because memories interfere with each other.

Proactive interference is one type of interference, where old memories disrupt the retrieval of new ones.

Retroactive interference is the second type, where new memories disrupt the retrieval of old ones.

Interference Theory suggests that the more similar two memories are, the more likely they are to interfere with each other.

The time interval between learning events also plays a crucial role.

Memories that are learned close together in time are more likely to interfere with each other than memories that are learned further apart.

Decoding proactive interference reveals the theory, but how does this play out in real life? Let’s examine some everyday scenarios where old memories stubbornly block the path to new ones. These examples will help solidify your understanding of proactive interference and its pervasive influence on our daily lives.

Proactive Interference in Action: Everyday Examples

Proactive interference isn’t an abstract concept confined to psychology textbooks. It manifests in our daily routines, often causing minor frustrations and occasional embarrassments. Let’s look at some common examples.

The Phone Number Predicament

Ever get a new phone number and find yourself repeatedly dialing your old one?

This is a classic example of proactive interference.

The memory of your old phone number is so deeply ingrained that it interferes with your ability to recall the new one.

Your brain has a well-established pathway for the old number, and it struggles to create a new, equally strong pathway for the updated information.

Each time you try to recall the new number, the old one pops up first, hijacking your retrieval process.

The Name Game

Another common manifestation of proactive interference occurs when you meet someone new and accidentally call them by the name of someone you already know.

Perhaps you call your new coworker "Sarah" because that’s the name of your best friend.

This isn’t just a random slip of the tongue.

The pre-existing memory of your friend Sarah’s name is actively interfering with your ability to recall the new acquaintance’s name.

The more familiar the old name, the stronger the interference.

This can be particularly embarrassing, highlighting the real-world social implications of memory interference.

The Tech Trap

Proactive interference can also plague our interactions with technology.

Imagine switching to a new version of a software program you’ve used for years.

Despite knowing the new interface and features, you constantly revert to the old commands and workflows.

Your past experience with the older version creates a cognitive roadblock, making it difficult to embrace the new system.

The well-worn neural pathways associated with the old software are so strong that they override your attempts to learn and apply the new ones.

This is why learning new software can be frustrating, even when the new version is objectively better.

Why These Are Proactive Interference Examples

These examples share a common thread: old information is hindering the retrieval or encoding of new information.

In each case, a previously learned piece of information—an old phone number, a familiar name, an outdated software command—is proactively interfering with your ability to recall or use the new, correct information.

It’s crucial to recognize that this isn’t simply forgetting.

It’s a specific type of memory failure where the existing memory is actively blocking the formation or retrieval of the new memory.

This distinction is key to understanding and addressing proactive interference effectively.

The Role of Encoding

Encoding, the process of converting information into a form that can be stored in memory, plays a crucial role in proactive interference.

If the initial encoding of the new information is weak, it becomes even more susceptible to interference from older, stronger memories.

For example, if you only half-heartedly pay attention when someone tells you their name, you’re more likely to call them by the wrong name later, especially if that wrong name is familiar to you.

Strong encoding involves paying attention, actively processing the information, and creating meaningful associations.

By strengthening the initial encoding of new information, you can reduce its vulnerability to proactive interference.

The more familiar the old name, the stronger its hold on your mental pathways, making it that much harder to retrieve the new one. But proactive interference is only one piece of the puzzle. Memory, as it turns out, is a battlefield where old and new information constantly vie for dominance.

Proactive vs. Retroactive Interference: Untangling the Confusion

While proactive interference shines a light on how old memories can hinder new ones, it’s crucial to understand that forgetting isn’t a one-way street. Retroactive interference presents a different, yet equally common, challenge: New information muddling the recall of older memories.

Decoding Retroactive Interference: New Information Obscuring the Old

Retroactive interference occurs when newly learned information interferes with your ability to recall previously learned information. Imagine learning a new software program at work. Initially, you might struggle, but eventually you master it.

Now, when you try to remember how to use the old software, you find yourself drawing a blank. The knowledge of the new program has overwritten, or at least obscured, your memory of the old one.

This is retroactive interference in action. The new information is working backward, retroactively, to disrupt your access to older memories.

Proactive vs. Retroactive: A Head-to-Head Comparison

The key difference between proactive and retroactive interference lies in the direction of the interference. In proactive interference, old information is the aggressor, attacking your ability to learn and recall new information. Think "past blocks present."

In retroactive interference, the roles are reversed. New information is the culprit, hindering your recall of old information. Think "recent blocks remote."

| Feature | Proactive Interference | Retroactive Interference |

|---|---|---|

| Direction | Old interferes with new | New interferes with old |

| Cause | Previously learned information | Recently learned information |

| Effect | Difficulty learning new things | Difficulty remembering old things |

Mnemonics: Mastering the Memory Minefield

Distinguishing between proactive and retroactive interference can be tricky, but mnemonics can help solidify the difference. Here are a couple of handy tricks:

- Proactive = Past interferes with present.

- Retroactive = Recent interferes with remote (old).

These simple associations can act as mental anchors, helping you quickly recall the core difference between the two types of interference.

Visual aids can also be helpful. Imagine two lines representing time. For proactive interference, draw an arrow from the past pointing towards the present, blocking it. For retroactive interference, draw an arrow from the present pointing towards the past, erasing it.

The Frustration Factor: You’re Not Alone

It’s undeniably frustrating when your memory fails you, whether due to proactive or retroactive interference. You are trying to recall critical information, but your brain seems to be actively working against you.

Know that these memory hiccups are incredibly common. They are a normal part of how our brains process and store information. Understanding the mechanisms behind these interferences can empower you to develop strategies to minimize their impact.

Proactive vs. Retroactive: A Head-to-Head Comparison

The key difference between proactive and retroactive interference lies in the direction of the interference. In proactive interference, old information is the aggressor, attacking your ability to learn and recall new information. Think "past blocks present."

In retroactive interference, the roles are reversed. New information is the culprit, working backward to disrupt your access to older memories. It’s "present blocks past." This crucial distinction helps clarify which type of interference is at play when you find yourself struggling with recall.

Proactive Interference Through the Lens of Cognitive Psychology and Memory

Cognitive psychology provides a powerful framework for understanding how proactive interference operates, moving beyond simple definitions to explore the underlying mechanisms and impact on our cognitive processes.

It’s not just about forgetting; it’s about how our minds organize, store, and retrieve information, and how these processes can be disrupted by previously learned material.

The Cognitive Approach to Proactive Interference

Cognitive psychologists employ a variety of research methods to investigate proactive interference. These methods include controlled laboratory experiments, often involving memory tasks with carefully designed stimuli, and computational modeling, which simulates cognitive processes to understand how interference arises.

These experiments often involve presenting participants with lists of items to remember, systematically varying the similarity between lists and measuring the impact on recall performance.

By manipulating factors such as the semantic relatedness of words or the temporal spacing between learning episodes, researchers can isolate the specific conditions that exacerbate or mitigate proactive interference.

The Impact on Long-Term Memory

While proactive interference can affect short-term memory, its effects are particularly pronounced on long-term memory (LTM). Think of your LTM as a vast library; if older information is poorly organized or too similar to new information, it can make finding the right "book" (memory) much harder.

The more similar the new information is to the old, the greater the interference.

This is why you might struggle to remember a new coworker’s name if it’s similar to the name of someone you’ve known for years. The old memory actively competes with the new, making it difficult for the new memory to consolidate and be retrieved effectively from your long-term storage.

Experimental Evidence: Delving into the Research

Numerous studies have demonstrated the robustness of proactive interference. For example, classic experiments by Underwood (1957) showed that the more lists of words participants had previously learned, the worse they performed on recalling a new list.

This cumulative effect highlights how past learning can progressively impair the acquisition of new memories.

More recent research has used neuroimaging techniques to examine the brain regions involved in proactive interference. These studies have found that areas of the prefrontal cortex, responsible for cognitive control and working memory, are particularly active when individuals are trying to overcome interference.

This suggests that our brains are actively working to suppress old memories and prioritize new ones, but this process requires cognitive effort and can be prone to failure, especially when the interference is strong.

The evidence consistently points to proactive interference as a significant factor influencing memory performance, emphasizing the need for strategies to minimize its impact on our daily lives.

Proactive interference can feel like a constant battle against your own mind, a frustrating struggle to learn and retain new information when old knowledge keeps getting in the way. Fortunately, it’s not an insurmountable obstacle. With the right strategies, you can minimize the impact of proactive interference and reclaim control over your memory.

Beating the Block: Strategies to Minimize Proactive Interference

While proactive interference can be a frustrating obstacle to learning, there are several evidence-based strategies you can implement to minimize its impact. These techniques focus on optimizing how you encode new information and strengthening the distinctiveness of existing memories.

Spaced Repetition: The Power of Time

One of the most effective techniques is spaced repetition. Instead of cramming information into a single, intense study session, distribute your learning over time.

Spacing out learning sessions allows your brain to consolidate new information more effectively. It also forces you to actively retrieve the information at each session, strengthening the memory trace and making it more resistant to interference.

Think of it like building a muscle: consistent, spaced-out workouts are far more effective than one marathon session.

Contextual Cues: Creating Mental Compartments

Our memories are often tied to the context in which they were formed. By using distinct cues or contexts for new information, you can create mental compartments that separate it from older, potentially interfering memories.

This could involve studying in a different location, using different study materials, or even associating the new information with a unique sensory experience, like a particular scent or sound.

The more distinct the context, the easier it will be to retrieve the new information without interference from the old.

For instance, if you’re learning a new language, try studying in a room dedicated solely to that activity, surrounded by books and materials related to the language.

Reinforcing the Old: Strengthening Memory Traces

Ironically, one way to protect new memories from proactive interference is to review and reinforce old information. This might seem counterintuitive, but strengthening the distinctiveness of older memories can actually reduce their tendency to interfere with new ones.

Regularly revisiting and testing yourself on previously learned material helps solidify those memories, making them less susceptible to being confused with new information.

This process sharpens the boundaries between old and new learning, reducing the likelihood of interference.

Consider regularly revisiting key concepts from previous courses or projects. The more distinct those memories are, the less likely they are to disrupt your current learning endeavors.

Minimizing Distractions: Focusing the Mind

Finally, minimizing distractions during the encoding process is crucial for preventing proactive interference. When you’re trying to learn something new, your brain needs to focus its full attention on the task at hand.

Distractions can disrupt the encoding process, making the new information weaker and more vulnerable to interference.

Create a quiet, dedicated learning environment free from interruptions. Turn off notifications on your phone and computer, and let others know that you need uninterrupted time to focus.

Finding What Works: Experimentation is Key

Ultimately, the best way to minimize proactive interference is to experiment with different strategies and find what works best for you. Everyone’s memory works a little differently, so what is highly effective for one person might not be as helpful for another.

Try different combinations of these techniques and pay attention to how well you’re able to learn and retain new information.

Keep a learning journal. Document your study habits and track your recall performance. What study environments work best? Which strategies yield the best results?

Be patient with yourself and don’t be afraid to adjust your approach as needed.

FAQs: Proactive Interference and Forgetting

This section answers common questions about proactive interference and how it affects your memory. We’ll explore examples and strategies to help you minimize its impact.

What exactly is proactive interference?

Proactive interference happens when old information disrupts your ability to remember new information. Essentially, previously learned material is interfering with your attempts to recall something recent. It’s a common reason why we forget things.

Can you give a proactive interference example?

Imagine you move to a new house but keep accidentally writing your old address on mail. The previously learned information (old address) is proactively interfering with your ability to recall the new address. Another proactive interference example could be trying to learn a new password after using the same one for years.

How is proactive interference different from retroactive interference?

Proactive interference is when old information interferes with new information. Retroactive interference is the opposite: new information interferes with your ability to remember old information. Think of it as past vs. present affecting your memory.

What can I do to reduce the effects of proactive interference?

Strategies include minimizing similar learning materials close together, practicing new information extensively, and using mnemonic devices. Regularly reviewing previously learned information can also strengthen those memories, making them less susceptible to being a proactive interference example.

Alright, that’s proactive interference example in a nutshell! Hopefully, you’ve got a better grasp on why your brain sometimes trips up. Go easy on yourself and maybe try some new study techniques. Good luck!