Jean Piaget, a pioneer in cognitive development, extensively studied how children’s understanding of rules and justice evolves. Piaget’s moral development, a cornerstone of developmental psychology, offers profound insights into this process. Moral reasoning, specifically as explored in his work, influences how children approach dilemmas. Educational settings, therefore, can benefit from understanding these stages to better foster ethical decision-making among young learners. Examining Piaget’s methodology provides a framework for observing and analyzing the shifts in children’s moral perspectives.

Jean Piaget, a name synonymous with developmental psychology, has indelibly shaped our understanding of how children’s minds evolve. His work transcends mere observation, providing a framework for comprehending the intricate processes that govern a child’s cognitive and moral maturation. This exploration will focus on one crucial aspect of his legacy: his theory of moral development.

Piaget: A Pioneer in Child Psychology

Piaget’s contributions to psychology are extensive and profound. He revolutionized the field by shifting the focus from solely observing behavior to understanding the underlying cognitive structures that drive it.

His meticulous observations and insightful interpretations laid the foundation for understanding how children construct knowledge and make sense of the world around them. His stage theory of cognitive development, though subject to revisions and refinements, remains a cornerstone of developmental psychology.

Defining Moral Development

Moral development refers to the process through which children develop a sense of right and wrong.

It encompasses the acquisition of values, beliefs, and principles that guide their behavior and shape their interactions with others. This development is not merely about learning rules; it involves a complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, and social factors.

Understanding moral development is paramount. It helps us understand how children learn to navigate the social world, resolve conflicts, and contribute to a just and equitable society.

Purpose: Decoding Piaget’s Theory

This article aims to provide a simplified yet comprehensive explanation of Piaget’s theory of moral development. By breaking down complex concepts into accessible language, we hope to offer valuable insights for educators, parents, and anyone interested in understanding the moral lives of children.

Our goal is to illuminate the key stages, concepts, and implications of Piaget’s work, making it relevant and applicable to real-world contexts. Understanding these principles offers guidance for nurturing ethical reasoning in young people.

Cognitive Foundations: How Piaget’s Stages Shape Moral Reasoning

Piaget’s theory of moral development is not an isolated framework; it is intrinsically linked to his broader theory of cognitive development.

Understanding the stages of cognitive development is essential because they provide the bedrock upon which moral reasoning is built. A child’s capacity for moral judgment is limited by their cognitive abilities at each developmental stage.

The Interplay of Cognitive and Moral Growth

Cognitive development provides the necessary tools for moral reasoning. For instance, the ability to understand abstract concepts, consider different perspectives, and engage in logical thought are all cognitive skills that directly influence moral decision-making.

Children’s moral judgments are not solely based on external rules; they are constructed through their interactions with the world, in tandem with their developing cognitive structures.

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development: A Brief Overview

To understand how cognitive development shapes moral reasoning, let’s briefly revisit Piaget’s stages of cognitive development:

-

Sensorimotor Stage (0-2 years): During this stage, infants learn about the world through their senses and actions. They lack object permanence early on, and their understanding of morality is virtually non-existent. Morality at this point is purely sensorimotor, driven by immediate needs and reflexes.

-

Preoperational Stage (2-7 years): Children in this stage are egocentric and struggle with logical thought. Their moral reasoning is typically based on objective consequences rather than intentions, reflecting heteronomous morality.

They also have trouble seeing things from another person’s perspective.

-

Concrete Operational Stage (7-11 years): Children begin to think logically about concrete events and grasp the concept of conservation. Their moral reasoning starts to shift towards considering intentions, although they still have a strong respect for rules and authority.

-

Formal Operational Stage (12+ years): Adolescents develop the ability to think abstractly and hypothetically. This allows them to engage in moral reasoning based on principles, values, and a deeper understanding of justice and fairness, aligning with autonomous morality.

Connecting Cognitive Stages to Moral Understanding

The progression through Piaget’s cognitive stages directly influences the development of moral understanding. For example:

A child in the preoperational stage may judge an act as "bad" solely based on the outcome, regardless of the actor’s intent. If a child accidentally breaks a vase while trying to help, they might perceive this as worse than intentionally scuffing a table out of anger, showcasing objective responsibility.

As they move into the concrete operational stage, they begin to consider intentions, recognizing that accidents are different from deliberate actions.

Finally, in the formal operational stage, adolescents can grapple with complex moral dilemmas, evaluating situations from multiple perspectives and applying abstract principles of justice and fairness.

They have developed the ability to think about morality in a more nuanced and sophisticated manner. This ability to use complex reasoning is a key development of the cognitive and moral stages and how they interplay.

Two Pillars of Moral Development: Heteronomous vs. Autonomous Morality

Having established the cognitive groundwork that shapes moral reasoning, we can now explore the two distinct stages that Piaget proposed to describe the development of morality itself. These stages, heteronomous morality and autonomous morality, represent a fundamental shift in how children perceive rules, justice, and the very nature of right and wrong. Understanding these stages provides invaluable insight into the evolving moral compass of a child.

Heteronomous Morality (Moral Realism/Constraint)

Heteronomous morality, also known as moral realism or morality of constraint, is the first stage in Piaget’s theory of moral development. This stage typically characterizes children aged 5 to 10, although the exact age range can vary. It is marked by a rigid adherence to rules and a belief that they are absolute and handed down by authority figures.

Rules as Fixed and Unchangeable

Children in this stage view rules as fixed and unchangeable decrees. They believe that rules come from authority figures such as parents, teachers, or God. Breaking a rule is seen as inherently wrong, regardless of the circumstances. There is a limited understanding that rules can be modified or created through mutual agreement.

Objective Responsibility Over Intentions

A key characteristic of heteronomous morality is the focus on objective responsibility. Children in this stage primarily consider the consequences of an action when judging its morality. The intention behind the action is largely ignored or given minimal consideration.

For example, a child who accidentally breaks several cups while trying to help is seen as more wrong than a child who breaks one cup while misbehaving, simply because the former caused more damage.

Moral Realism and the Expectation of Punishment

The concept of moral realism is central to heteronomous morality. Children believe that rules are real, objective entities, much like physical laws.

They also believe that breaking a rule will inevitably lead to punishment. This belief is often rooted in the idea of immanent justice, where any transgression will automatically be followed by negative consequences, even if no one else is aware of the misdeed.

Justice in the Heteronomous Stage

Justice, in this stage, is understood as expiatory punishment. The primary goal of punishment is to make the offender suffer in proportion to the damage caused.

The concept of fairness is often linked to strict equality, where everyone receives the same treatment regardless of individual circumstances. Restitution or making amends for the harm caused is not a central focus.

Autonomous Morality (Moral Relativism/Cooperation)

Autonomous morality, also known as moral relativism or morality of cooperation, is the second stage in Piaget’s theory. It typically emerges around the age of 10 or 11 and continues to develop through adolescence. This stage is characterized by an understanding that rules are made by people and can be changed through mutual agreement.

Rules as Mutable Agreements

Children in the stage of autonomous morality understand that rules are not absolute laws but rather agreements created by people. They recognize that rules can be modified or even abolished if the people involved agree to do so. This understanding arises from increased social interaction and cooperation with peers.

Shifting Focus to Intentions

In contrast to heteronomous morality, intentions become crucial in evaluating actions. Children begin to understand that the reasons behind an action are just as important, if not more so, than the consequences.

An accidental transgression is viewed differently from a deliberate act of harm. This ability to consider intentions marks a significant advancement in moral reasoning.

Moral Relativism and Contextual Understanding

Moral relativism becomes a defining feature of this stage. Children understand that there isn’t always one right answer and that moral judgments can vary depending on the context and the individuals involved. They recognize that different people may have different perspectives and that these perspectives should be considered.

Justice Rooted in Equity and Reciprocity

Justice is no longer seen as simply expiatory punishment. Instead, it is understood in terms of equity and reciprocity. Punishment should be proportionate to the offense and should aim to repair the harm caused. The focus shifts toward understanding the offender’s motives and circumstances.

The Role of Cooperation and Mutual Respect

Cooperation and mutual respect are essential for developing autonomous morality. Through interactions with peers, children learn to negotiate, compromise, and understand different viewpoints. These experiences foster a sense of fairness and justice based on mutual understanding rather than blind obedience to authority. They begin to internalize moral principles based on respect for others and a desire for harmonious relationships.

Having explored the distinct characteristics of heteronomous and autonomous morality, it becomes crucial to dissect the fundamental concepts that underpin these stages. These concepts – rules, justice, intentions, and punishment – are not static; their understanding evolves dramatically as children transition from a morality of constraint to one of cooperation.

Dissecting the Concepts: Rules, Justice, Intentions, and Punishment Through Piaget’s Lens

At the heart of Piaget’s theory lies a profound shift in how children perceive the very fabric of their social world. To truly grasp this evolution, we must delve into the nuances of moral realism and moral relativism and examine how the understanding of key elements – rules, justice, punishment, and intentions – transforms across the stages of moral development.

Moral Realism vs. Moral Relativism: A Shifting Worldview

The transition from heteronomous to autonomous morality is, in essence, a journey from moral realism to moral relativism.

Moral Realism: The Immutability of Rules

In moral realism, characteristic of the heteronomous stage, children believe that rules are absolute, objective, and exist independently of human agreement.

They are perceived as external entities, much like physical laws, handed down by authority figures.

Breaking a rule is inherently wrong, regardless of the context or intention. This stems from a cognitive constraint where children struggle to understand rules as social conventions.

Moral Relativism: Rules as Social Constructs

In contrast, moral relativism, which emerges during the autonomous stage, reflects an understanding that rules are created by people and can be modified or even discarded through mutual agreement.

Children begin to recognize that rules are not absolute truths but rather social constructs designed to facilitate cooperation and fairness.

This shift is accompanied by a greater appreciation for the context surrounding actions and the intentions behind them.

The Evolving Role of Rules

The understanding of rules undergoes a significant transformation.

In the heteronomous stage, rules are seen as sacred and inviolable.

Children rigidly adhere to them, often focusing on the letter of the law rather than its spirit.

With the advent of autonomous morality, children view rules as flexible guidelines that can be adapted to suit specific situations.

They begin to appreciate the importance of mutual agreement and cooperation in establishing and maintaining rules.

This understanding allows for a more nuanced and flexible approach to moral decision-making.

Justice: From Expiatory to Reciprocal

The concept of justice also evolves dramatically.

In the heteronomous stage, justice is often viewed as expiatory, meaning that punishment should be proportional to the damage caused, regardless of intention.

The focus is on retribution rather than rehabilitation or understanding.

As children transition to autonomous morality, they develop a more reciprocal understanding of justice.

They recognize that justice should be fair, equitable, and take into account the intentions and circumstances of the individual.

This understanding leads to a greater emphasis on empathy, forgiveness, and restorative justice.

Intentions: Unveiling the Moral Compass

Perhaps the most significant shift in moral reasoning involves the understanding of intentions.

In the heteronomous stage, children primarily focus on the objective consequences of an action, largely ignoring the intentions behind it.

A child who accidentally breaks ten cups is seen as having committed a more serious transgression than a child who intentionally breaks one cup.

As children develop autonomous morality, they begin to recognize the crucial role of intentions in evaluating actions.

They understand that an action with good intentions but unintended negative consequences may be morally excusable, while an action with malicious intentions is morally reprehensible, even if the consequences are minor.

This ability to consider intentions marks a significant leap in moral maturity.

Punishment: A Shift in Perspective

The purpose and application of punishment are also viewed differently across the two stages.

In the heteronomous stage, punishment is seen as a necessary consequence of breaking a rule, with the primary goal of retribution.

Children believe that punishment should be severe and directly related to the damage caused.

There is little emphasis on understanding the reasons behind the transgression or on rehabilitating the offender.

In the autonomous stage, children recognize that punishment should be fair, consistent, and aimed at helping the offender understand the wrongfulness of their actions and make amends.

The focus shifts from retribution to rehabilitation, with an emphasis on empathy, forgiveness, and restorative justice.

Punishment is viewed as a means of promoting moral growth and preventing future transgressions, rather than simply as a means of exacting revenge.

Having explored the distinct characteristics of heteronomous and autonomous morality, it becomes crucial to dissect the fundamental concepts that underpin these stages. These concepts – rules, justice, intentions, and punishment – are not static; their understanding evolves dramatically as children transition from a morality of constraint to one of cooperation.

Bringing Theory to Life: Real-World Examples of Moral Development

Piaget’s theory, while insightful, can feel abstract without tangible examples. To truly appreciate the developmental leap children make in their moral reasoning, it’s essential to examine how these stages manifest in everyday situations.

By grounding the theory in real-world scenarios, we can make it more relatable and understandable, especially for educators and parents seeking to support children’s moral growth.

Heteronomous Morality in Action: A Focus on Consequences

In the heteronomous stage, a child’s moral judgment is heavily influenced by the observable consequences of an action, rather than the intentions behind it.

Imagine two scenarios:

- A child accidentally breaks a vase while trying to help their parent.

- Another child intentionally breaks a toy belonging to a sibling in a fit of anger.

A child in the heteronomous stage is likely to perceive the first child as more wrong because the vase is more valuable than the toy. The focus is on the damage done, not the intention behind the act.

This is because children in this stage struggle with abstract thinking and perspective-taking.

They have difficulty understanding that unintentional actions can be less blameworthy than intentional ones, even if the outcome is more severe.

The Broken Cookie Jar: A Classic Example

Consider a child who climbs a chair to reach a cookie jar against their parent’s instructions, and subsequently falls, breaking the jar.

In the heteronomous stage, the child views their wrongness as rooted in two things. First, disobedience, which is an act that can attract punitive interventions from authority.

Second, the cookie jar breaking, a consequence that demonstrates they must be punished for their actions.

The focus isn’t on the intention (wanting a cookie), but the outcome (a broken cookie jar) and the rule (don’t climb the chair to reach the cookie jar).

This highlights the core tenet of heteronomous morality: rules are absolute, and consequences determine culpability.

Autonomous Morality in Practice: Understanding Intentions

As children transition to autonomous morality, their moral reasoning becomes more nuanced. They begin to understand that intentions matter.

Using the previous scenarios, a child in the autonomous stage would likely evaluate the first child (breaking the vase accidentally) with more leniency.

They recognize that the child’s intention was helpful, and the accident was unintentional.

In contrast, they would likely view the second child (breaking the toy intentionally) as more culpable, even though the damage was less severe.

This is because they understand that the intention behind the act was malicious.

Sharing Toys: A Lesson in Cooperation

Consider two children playing with building blocks. One child has many blocks, and the other has very few.

A child in the autonomous stage might suggest sharing the blocks to ensure both children can build something enjoyable.

This demonstrates an understanding of fairness, equality, and cooperation, key components of autonomous morality.

They can understand that sharing promotes mutual enjoyment and strengthens social bonds.

This type of reasoning moves beyond simple rule-following and considers the impact of actions on others’ well-being.

Scenarios for Comparison: Highlighting the Shift

To further illustrate the differences, let’s analyze a few more scenarios.

Lying: Telling a "White Lie" vs. a Malicious Deception

A child in the heteronomous stage would likely view any lie as equally wrong, regardless of the motivation.

Conversely, a child in the autonomous stage will recognize the distinction between "white lies" (told to protect someone’s feelings) and malicious lies (told to harm someone).

The shift here is a progression to assessing intent, not just the objective adherence to a rule (in this case, telling the truth).

Stealing: Stealing Food to Survive vs. Stealing for Personal Gain

A heteronomous perspective would likely condemn all instances of stealing without considering the circumstances.

An autonomous view would consider the motivation behind the act.

Stealing food to survive in a desperate situation might be seen as more justifiable (though still wrong) than stealing for personal enrichment.

The Importance of Context and Perspective

These real-world examples underscore the importance of context and perspective in moral development. Piaget’s theory helps us understand how children progress from a rigid, consequence-oriented understanding of morality to a more flexible, intention-based approach.

By recognizing these stages, parents and educators can tailor their guidance to support children’s moral growth, fostering empathy, cooperation, and a deeper understanding of right and wrong.

Having grounded the theory in real-world scenarios, we can make it more relatable and understandable, especially for educators and parents seeking to support children’s moral growth. However, as with any influential theory, it’s crucial to acknowledge the criticisms and limitations that temper its application. While Piaget’s framework offers a valuable lens through which to view moral development, it’s not without its shortcomings, which warrant careful consideration.

Critiques and Considerations: Examining the Limitations of Piaget’s Theory

While Jean Piaget’s theory of moral development has provided invaluable insights into how children’s understanding of morality evolves, it’s essential to acknowledge the criticisms and limitations associated with his framework.

These critiques often center on potential underestimations of children’s abilities and the need for further research to refine and expand upon his initial findings.

By acknowledging these limitations, we can approach Piaget’s theory with a more nuanced perspective and avoid oversimplifying the complexities of moral development.

The Underestimation of Children’s Moral Reasoning

One of the most prominent criticisms of Piaget’s theory revolves around the potential underestimation of children’s moral reasoning abilities, particularly in the earlier stages.

Critics argue that Piaget’s experimental methods and the types of moral dilemmas he presented may not have been fully accessible to young children.

These methodologies may have inadvertently masked their true capacity for understanding intentions and considering multiple perspectives.

Specifically, some researchers suggest that children may be able to grasp more complex moral concepts if presented with scenarios that are more relatable and less abstract.

Furthermore, the language used in Piaget’s interviews may have been too complex for younger children to fully comprehend, leading to inaccurate assessments of their moral reasoning.

Cultural and Contextual Factors

Another limitation of Piaget’s theory lies in its relative neglect of cultural and contextual factors that can significantly influence moral development.

Piaget’s research was primarily conducted with children from Western cultures, and his stages may not accurately reflect the moral development of children in other cultural contexts.

Different cultures may have varying values, norms, and social practices that shape children’s understanding of morality in unique ways.

For example, some cultures may place a greater emphasis on collective responsibility and social harmony, while others may prioritize individual rights and autonomy.

These cultural differences can affect how children interpret rules, perceive justice, and respond to moral dilemmas.

Therefore, it’s essential to consider the cultural context when applying Piaget’s theory to children from diverse backgrounds.

The Role of Social Interaction

While Piaget acknowledged the importance of social interaction in promoting moral development, some critics argue that he underestimated its crucial role.

Social interactions, particularly with peers, provide children with opportunities to engage in moral discussions, negotiate rules, and resolve conflicts.

These experiences can foster perspective-taking, empathy, and a deeper understanding of moral principles.

Furthermore, interactions with adults, such as parents and teachers, can also play a vital role in shaping children’s moral values and beliefs.

Adults can provide guidance, model moral behavior, and create a supportive environment for children to explore moral issues.

Therefore, a more comprehensive theory of moral development should give greater emphasis to the complex interplay between cognitive development and social interaction.

Areas for Further Research

Despite its limitations, Piaget’s theory has stimulated a wealth of research on moral development, and there are still many areas that warrant further exploration.

One area is the development of moral emotions, such as guilt, shame, and empathy, and how these emotions influence moral behavior.

Another is the role of moral identity in shaping individuals’ commitment to moral values and their willingness to act ethically.

Additionally, further research is needed to understand the neural mechanisms underlying moral reasoning and decision-making.

By addressing these questions, we can gain a more complete understanding of the complex processes involved in moral development.

In conclusion, while Piaget’s theory of moral development offers a valuable framework for understanding how children’s moral reasoning evolves, it’s crucial to acknowledge its limitations and consider alternative perspectives. By doing so, we can gain a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the complexities of moral development and better support children’s moral growth.

Piaget’s Moral Development: Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some common questions about Piaget’s theory of moral development, aimed at clarifying the concepts discussed.

What are the key stages in Piaget’s moral development theory?

Piaget outlined two primary stages. The first is moral realism or heteronomous morality, where rules are seen as absolute and unbreakable. The second is moral relativism or autonomous morality, where individuals understand that rules are made by people and can be changed.

What’s the difference between moral realism and moral relativism?

Moral realism focuses on the consequences of an action rather than the intent. Rules are handed down by authority and must be obeyed strictly. Moral relativism, in contrast, considers intent and circumstances, understanding that rules are flexible and agreed upon socially.

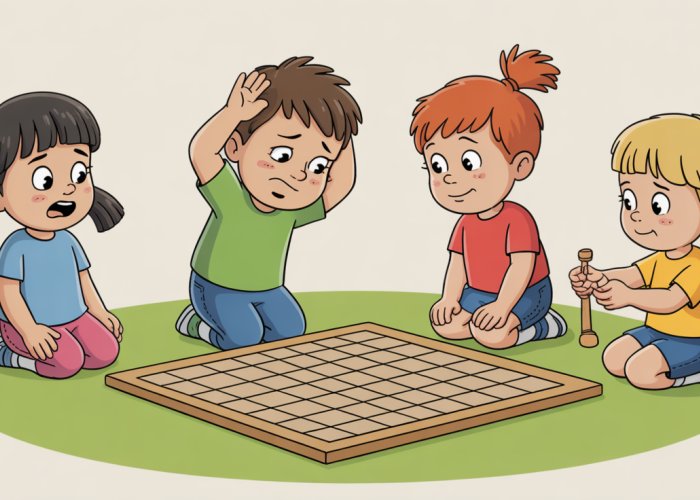

How does playing games influence piaget’s moral development?

Piaget believed that playing games with rules is critical. Through game play, children learn to negotiate, cooperate, and understand that rules can be modified by mutual consent. This understanding is fundamental to the shift from moral realism to moral relativism.

At what age do children typically transition into moral relativism, according to Piaget?

While ages can vary, Piaget suggested that children typically begin to transition into the stage of moral relativism around age 10 or 11. This transition coincides with the development of more advanced cognitive abilities allowing them to reason more abstractly about piaget’s moral development.

And that’s the simple breakdown of Piaget’s moral development! Hopefully, this made the concept a little clearer. Now you can apply what you’ve learned and maybe even spark some interesting conversations about ethics. Until next time!