Understanding classical sonata form is essential for any serious student of music. Mozart, a prominent composer, frequently utilized exposition, development, and recapitulation, the key sections of this form, to structure his compositions. The Juilliard School, known for its rigorous curriculum, emphasizes a deep understanding of classical sonata form as fundamental to music theory. Analysis of Beethoven’s symphonies further illuminates the nuanced application of this structure. Therefore, a thorough grasp of classical sonata form provides a robust foundation for both performance and musicological study.

Sonata Form stands as a monumental achievement in musical architecture, a blueprint that has shaped countless compositions and continues to resonate with audiences today. It’s more than just a structure; it’s a dynamic narrative, a journey of thematic exploration and resolution. Understanding Sonata Form unlocks a deeper appreciation for the intricacies of classical music and provides a framework for analyzing its expressive power.

Sonata Form: A Cornerstone of Classical Music

At its core, Sonata Form is a musical structure most commonly applied to the first movement of multi-movement works like symphonies, sonatas, and concertos. Think of it as a template, a set of guidelines that composers use to organize their musical ideas.

This doesn’t mean that every Sonata Form movement sounds the same. Far from it. Composers inject their own creativity and personality into the form, resulting in a vast range of musical experiences.

The form’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to balance structure and freedom, providing a framework for both logical development and emotional expression.

The Classical Period: Sonata Form’s Golden Age

Sonata Form truly flourished during the Classical Period (roughly 1750-1820). Composers like Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven embraced the form, using it as a vehicle for their innovative and expressive ideas.

It became the dominant structural principle, influencing not only instrumental music but also operatic and vocal works. The Classical Period witnessed Sonata Form evolve and refine, becoming the sophisticated and versatile structure we recognize today.

It’s important to remember that the "rules" of Sonata Form weren’t codified until after the Classical Period. Music theorists analyzed the works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, identifying common structural patterns and formalizing them into what we now call Sonata Form.

Navigating This Exploration

This exploration aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of Sonata Form. We will dissect its various sections, examining their individual roles and how they contribute to the overall form.

We’ll delve into the thematic development, harmonic language, and expressive potential of each section, giving you the tools to analyze and appreciate Sonata Form in a wide range of musical contexts. By the end of this journey, you’ll be equipped to recognize Sonata Form in action and understand its enduring significance in the world of music.

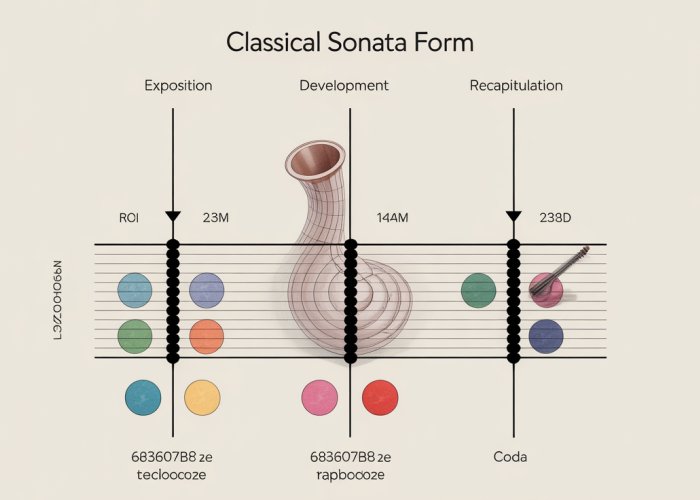

Deconstructing Sonata Form: The Exposition

As Sonata Form unfolds, the first major section we encounter is the Exposition. This is where the composer lays out the musical landscape, introducing the primary thematic material that will be explored and developed throughout the movement.

Think of the Exposition as the opening chapter of a novel, where the main characters and setting are first introduced. It establishes the fundamental musical ideas and sets the stage for the drama to come.

Theme 1: Establishing the Tonic

The Exposition typically begins with Theme 1, also known as the Primary Theme. This theme is presented in the tonic key, the home key of the movement.

Theme 1 serves to establish the tonal center and provides a recognizable melodic and rhythmic identity. It’s often assertive and memorable, designed to capture the listener’s attention.

The character of Theme 1 can vary greatly, ranging from bold and triumphant to lyrical and introspective, depending on the composer’s intent. However, its primary function remains the same: to firmly establish the tonic key.

The Transition: Bridging the Gap

Following Theme 1, we encounter the Transition, sometimes referred to as the Bridge. Its primary purpose is to modulate, or change, from the tonic key to a new key, usually the dominant (for major keys) or relative major (for minor keys).

The Transition often involves unstable harmonies and a sense of increasing tension, creating anticipation for the arrival of Theme 2.

It might develop fragments of Theme 1 or introduce new melodic ideas, but its defining characteristic is its directional momentum towards the new key.

Theme 2: A Contrasting Perspective

The arrival of Theme 2, or the Secondary Theme, marks a significant shift in the musical landscape. Presented in the dominant or relative major key, it provides a contrasting melodic and harmonic perspective to Theme 1.

Theme 2 often offers a lyrical or more relaxed character compared to the assertive Theme 1. This contrast is crucial for creating musical interest and highlighting the inherent tension within the Sonata Form.

The relationship between Theme 1 and Theme 2 is a key element of the Exposition. Their contrasting characters and tonal relationships provide the raw material for the dramatic development that follows.

Closing Theme and Codetta (Optional)

The Exposition may conclude with an optional closing theme or codetta. This section serves to solidify the new key and bring the Exposition to a satisfying close.

A closing theme typically presents a concise and memorable melody that reinforces the tonality of Theme 2.

A codetta, a small coda, acts as a brief concluding passage, often featuring repetitive rhythmic or melodic figures.

Whether a closing theme or codetta is present, their function is the same: to provide a sense of finality and prepare the listener for the subsequent Development section.

The Development: Where Themes Transform

With the Exposition behind us, the musical narrative takes a dramatic turn. The Development section arrives, serving as the heart of the Sonata Form’s journey. Here, the composer embarks on a voyage of exploration and transformation, taking the thematic material introduced earlier and subjecting it to a series of inventive manipulations.

Unveiling the Essence of Development

The Development is characterized by its harmonic instability and its adventurous spirit. Unlike the Exposition, which firmly establishes tonal centers, the Development revels in ambiguity. It often begins in the key of the dominant (or relative major), but quickly ventures into more distant and unexpected harmonic territories. This creates a sense of tension and anticipation.

It leaves the listener uncertain about the ultimate destination.

The primary goal of the Development is to explore the potential inherent in the themes presented in the Exposition. It’s a playground where the composer can dissect, recombine, and reimagine the original material in surprising ways.

Techniques of Thematic Transformation

Composers employ a variety of techniques to achieve this thematic transformation:

- Fragmentation: Breaking down themes into smaller motives or fragments.

- Alteration: Changing the melody, rhythm, or harmony of a theme.

- Inversion: Turning a melody upside down.

- Retrograde: Playing a melody backwards.

- Augmentation: Lengthening the note values of a theme.

- Diminution: Shortening the note values of a theme.

- Sequence: Repeating a melodic fragment at a different pitch level.

These techniques allow the composer to create a sense of constant evolution and discovery. A familiar theme might be stripped down to its bare essentials. Then presented in a new and unexpected light.

Or it might be combined with elements of other themes. This can lead to complex and fascinating musical textures.

The Role of Key Modulation and Harmonic Instability

Key modulation is paramount in the Development. The music frequently shifts from one key to another, often without warning. These rapid key changes contribute to the overall feeling of instability and unrest. It keeps the listener engaged and prevents the music from becoming predictable.

Harmonic instability is further enhanced by the use of dissonances and unresolved chords. The composer deliberately avoids providing a clear sense of tonal resolution. That is until the arrival of the Recapitulation.

This creates a feeling of suspense and anticipation. A listener anticipates the eventual return to the tonic key.

The Development, therefore, is not merely a repetition of the Exposition. It is a dynamic and transformative process. The journey takes the listener through a landscape of shifting harmonies and evolving themes. This ultimately prepares them for the satisfying return of the original material in the Recapitulation.

The manipulation of thematic material, the daring harmonic shifts, and the overall sense of exploration within the Development section inevitably lead us back to familiar territory. But this isn’t simply a rote repetition of what came before. The journey through the Development has fundamentally altered our perception, setting the stage for a return that is both comforting and subtly transformed. This return manifests in the Recapitulation.

Recapitulation: A Return, But Not Identical

The Recapitulation, the third major section of Sonata Form, provides a sense of resolution. It’s a homecoming for the themes introduced in the Exposition, but the landscape has changed. The harmonic tensions built up in the Development are now addressed, and the themes return with a newfound stability.

The Essence of Recapitulation

The core function of the Recapitulation is to restate the Exposition’s thematic material, but with a crucial difference: everything now resides in the tonic key. This provides a sense of harmonic closure, resolving the tonal conflicts introduced earlier.

Theme 1: A Familiar Landmark

The Recapitulation begins with the return of Theme 1 (the Primary Theme), presented once again in the tonic key. This immediately establishes a feeling of familiarity and stability. It’s like returning to a well-known landmark after a long journey. The listener is anchored back in the home key.

The Transition’s Transformation

The Transition (or Bridge), which in the Exposition modulated to a new key, undergoes a significant alteration in the Recapitulation. Instead of leading away from the tonic, the Transition is modified to remain within the tonic key. This crucial change prepares the listener for the arrival of the second theme without altering the harmonic center.

Theme 2: Resolution in the Tonic

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the Recapitulation is the restatement of Theme 2 (the Secondary Theme) in the tonic key. In the Exposition, this theme appeared in the dominant (or relative major) key, creating a sense of contrast.

By bringing Theme 2 into the tonic, the Recapitulation resolves the initial harmonic tension and provides a sense of unity. Both primary and secondary themes now coexist within the same tonal realm.

This shift gives the Recapitulation its unique character. It is not a mere copy of the Exposition, but a reimagining of it in light of the Development’s transformative journey.

The themes are familiar, yet their context has changed, offering a satisfying sense of closure and resolution. The Recapitulation serves as a critical step in providing a sense of completion, solidifying the listener’s understanding of the journey’s narrative.

The Coda: Providing a Sense of Closure

Having navigated the thematic development and harmonic resolution of the Recapitulation, we arrive at a point where the musical narrative could conceivably conclude. However, many composers choose to extend the journey, adding a final flourish that solidifies the sense of completion and provides a satisfying departure: the Coda.

The Role and Function of the Coda

The Coda, Italian for "tail," is an optional section that appears at the very end of a musical piece, particularly common in Sonata Form movements. Think of it as the final chapter in a compelling novel or the concluding scene of a captivating play.

Its primary function is to provide a definitive and resounding sense of closure. It goes beyond simply ending the piece; it reinforces the tonic key, reiterates important thematic material, and leaves the listener with a lasting impression of resolution.

While the Recapitulation resolves the harmonic tensions introduced in the Exposition and Development, the Coda offers a space for further affirmation and celebration of the established tonal stability.

Emphasizing Finality and Closure

Techniques for Achieving Closure

Composers employ various techniques to achieve this sense of finality within the Coda.

One common approach is to reiterate key thematic elements, often fragments of the primary theme, in a clear and unambiguous manner. This reinforces the listener’s memory of the core musical ideas and solidifies their connection to the tonic key.

Harmonic Reinforcement

Harmonic reinforcement is another crucial aspect. The Coda typically features a strong and prolonged emphasis on the tonic chord, often through repeated cadences and stable harmonic progressions.

This harmonic grounding further anchors the music in the home key, leaving no doubt about the piece’s ultimate resolution.

Cadenza-Like Passages

In some instances, the Coda might incorporate cadenza-like passages, showcasing the virtuosity of the performer while simultaneously building towards a powerful and conclusive ending.

These passages, while often technically demanding, serve to heighten the sense of excitement and anticipation before the final resolution.

The Coda: More Than Just an Ending

It’s important to understand that the Coda is not merely an afterthought or a tacked-on appendage.

When skillfully integrated, it serves as an integral part of the overall structure, enhancing the impact and memorability of the entire composition.

By providing a sense of finality and closure, the Coda ensures that the listener departs from the musical experience with a feeling of satisfaction and completeness.

A Historical Perspective: Sonata Form in the Classical Era

Having explored the architecture of the Coda and its contribution to the overall sense of completion, it’s time to step back and consider the historical context in which Sonata Form truly flourished. Its evolution is intrinsically linked to the Classical Period, a time of profound artistic and intellectual change that shaped not only musical forms but also the very way music was conceived and consumed.

The Genesis of Sonata Form in the Classical Period (c. 1750-1820)

Sonata Form didn’t emerge fully formed overnight.

Instead, it was a gradual evolution from earlier Baroque binary forms.

The Classical Period, roughly spanning from 1750 to 1820, provided fertile ground for its development.

This era was characterized by a focus on clarity, balance, and proportion, reflecting the Enlightenment ideals of reason and order.

Defining Characteristics of the Classical Style

The Classical style, with its emphasis on melodic simplicity, clear harmonic structures, and balanced phrasing, naturally lent itself to the development of Sonata Form.

Composers sought to create music that was both intellectually stimulating and emotionally engaging.

Sonata Form provided a framework for achieving this balance, allowing for both dramatic tension and satisfying resolution.

The focus shifted from the ornate complexities of the Baroque to a more streamlined and accessible musical language.

From Binary to Sonata: Tracing the Evolution

The seeds of Sonata Form can be found in the binary forms of the Baroque era.

These earlier forms typically consisted of two sections, each repeated, with a modulation to the dominant key in the first section and a return to the tonic in the second.

Classical composers expanded upon this basic structure, adding a Development section that allowed for greater thematic exploration and harmonic instability.

This addition was crucial in transforming the binary form into the more complex and dynamic Sonata Form we recognize today.

Key Composers and Early Experiments

Early Classical composers like Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Johann Christian Bach played a crucial role in experimenting with and refining these emerging structures.

They began to develop the characteristic features of Sonata Form.

This included clearly defined thematic areas, contrasting keys, and a more sophisticated approach to thematic development.

While their works may not fully adhere to the "textbook" definition of Sonata Form, they represent important stepping stones in its evolution.

The Rise of Instrumental Music

The Classical Period witnessed a significant rise in the popularity and importance of instrumental music.

The symphony, sonata, and string quartet became central genres, providing composers with ample opportunities to explore the potential of Sonata Form.

Unlike vocal music, which was often constrained by the demands of the text, instrumental music allowed for greater freedom of expression and experimentation.

Composers could focus on the purely musical aspects of form, harmony, and melody, pushing the boundaries of Sonata Form in new and exciting directions.

Sonata Form as a Narrative Framework

Beyond its structural characteristics, Sonata Form can be understood as a kind of musical narrative.

The Exposition introduces the main characters (themes) and establishes the dramatic conflict (the modulation to a new key).

The Development explores the implications of this conflict, taking the themes on a journey of transformation and instability.

Finally, the Recapitulation resolves the conflict, bringing the themes back to the tonic key and restoring a sense of order and balance.

This narrative framework provided composers with a powerful tool for creating compelling and engaging musical experiences.

The Masters of Sonata Form: Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven

Having charted the historical rise of Sonata Form and its defining characteristics, it’s crucial to examine the composers who elevated it to its artistic zenith. Three figures stand out as pillars of the Classical era and masters of this form: Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Ludwig van Beethoven. Their individual approaches and innovations shaped the very landscape of Sonata Form, leaving an indelible mark on music history.

Joseph Haydn: The Architect of Sonata Form

Joseph Haydn is often hailed as the "father" of the symphony and string quartet, and his contributions to the development of Sonata Form are equally significant. He didn’t invent the form outright, but rather refined and standardized it, setting the stage for future generations.

Haydn’s genius lay in his ability to create compelling musical narratives within the framework of Sonata Form. He possessed a keen understanding of harmonic structure and thematic development.

Haydn’s Approach to Thematic Development

Haydn’s approach to thematic development was particularly noteworthy. He frequently used motivic development, taking short musical ideas and transforming them throughout a movement.

This technique, where a small fragment of a theme is expanded, altered, and explored, provided unity and coherence to his compositions. His symphonies, particularly those written for London, showcase his mastery of Sonata Form.

They exhibit a clear and balanced architecture, with memorable melodies and engaging musical dialogues. Haydn’s sense of humor and wit also shine through in his compositions, often surprising listeners with unexpected twists and turns within the established form.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Elegance and Perfection

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart possessed an unparalleled gift for melody and a natural understanding of musical form. He absorbed the lessons of Haydn and refined them further, creating works of breathtaking beauty and elegance.

Mozart’s application of Sonata Form is characterized by its clarity, balance, and lyrical grace. His symphonies, concertos, and sonatas are models of Classical perfection.

Mozart’s Operatic Influence

Mozart’s background in opera also influenced his approach to Sonata Form. He understood how to create dramatic tension and release through musical means, often imbuing his instrumental works with a sense of narrative drama.

His concertos, in particular, demonstrate his ability to blend the structure of Sonata Form with the virtuosity of a solo instrument. The piano concertos, such as No. 21 in C major, K. 467, exemplify this.

They feature seamless transitions between the orchestral exposition and the solo instrument’s entrance, creating a captivating dialogue between the two. Mozart’s genius was in making the complexities of Sonata Form sound effortless.

Ludwig van Beethoven: The Revolutionary

Ludwig van Beethoven inherited the legacy of Haydn and Mozart but pushed the boundaries of Sonata Form in unprecedented ways. He infused the form with a new sense of drama, intensity, and emotional depth.

Beethoven’s music reflects the changing social and political climate of his time. He challenged the established norms of the Classical era.

Beethoven’s Dramatic Innovations

Beethoven’s use of dynamic contrast, rhythmic drive, and harmonic experimentation transformed Sonata Form into a vehicle for expressing powerful emotions. His symphonies, particularly the Third (Eroica) and Fifth, are revolutionary works that redefined the possibilities of the form.

He expanded the scale of the symphony, lengthened the development section, and introduced new levels of complexity to the thematic development. Beethoven wasn’t afraid to break the rules.

His innovations, like the extended Coda in the Eroica Symphony, significantly expanded the emotional weight and scope of the movement. Beethoven used Sonata Form as a framework for profound artistic expression, paving the way for the Romantic era.

Having explored the individual contributions of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven to the evolution of Sonata Form, a natural question arises: how does this form manifest itself in actual compositions? Examining specific musical examples allows us to move beyond theoretical definitions and appreciate the practical application of Sonata Form in some of the most celebrated works of the Classical and Romantic periods.

Sonata Form in Action: Notable Musical Examples

To truly grasp the essence of Sonata Form, one must venture beyond theoretical definitions and delve into the realm of practical application. Let’s explore several landmark compositions that showcase the form’s versatility and enduring appeal.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67: A Masterclass in Sonata Form

Perhaps no other work exemplifies Sonata Form as powerfully as the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5.

The iconic opening motif, a mere four notes, serves as the primary theme and permeates the entire movement.

The exposition unfolds with a dramatic contrast between the forceful primary theme and the more lyrical secondary theme, presented in the relative major key (E-flat major).

Beethoven masterfully utilizes the development section to fragment and transform the opening motif, creating a sense of intense struggle and harmonic tension.

The recapitulation brings back both themes, now firmly rooted in the tonic key of C minor and C major, respectively, providing a resolution to the preceding conflict.

A substantial coda further solidifies the sense of closure, driving the movement to its triumphant conclusion.

Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 16 in C major, K. 545: Elegance and Clarity

In stark contrast to Beethoven’s dramatic intensity, Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 16 provides a model of Classical elegance and clarity within the Sonata Form framework.

The exposition features a bright and cheerful primary theme in C major, followed by a graceful secondary theme in the dominant key of G major.

Mozart’s genius lies in his ability to create memorable melodies and seamless transitions between thematic areas.

The development section explores the thematic material with characteristic grace and refinement, showcasing Mozart’s mastery of counterpoint.

The recapitulation brings back the themes in the tonic key, providing a satisfying sense of balance and symmetry.

The movement concludes with a charming coda, rounding off the musical narrative with a touch of playful wit.

Haydn’s Symphony No. 104 in D major, "London": Architectonic Brilliance

Haydn, often regarded as the "father" of the symphony, demonstrates his architectonic brilliance in his Symphony No. 104.

The first movement showcases a clear and balanced Sonata Form structure, with distinct thematic areas and engaging musical dialogues.

The exposition presents a stately primary theme in D major, followed by a contrasting secondary theme in the dominant key of A major.

Haydn’s use of motivic development, where short musical ideas are transformed and expanded, provides unity and coherence to the movement.

The development section explores the thematic material with Haydn’s characteristic wit and ingenuity.

The recapitulation brings back the themes in the tonic key, solidifying the sense of resolution.

A lively coda brings the movement to a satisfying conclusion, showcasing Haydn’s mastery of orchestration and his ability to create music that is both intellectually stimulating and emotionally engaging.

The Enduring Legacy: Sonata Form’s Influence on Music

Having explored the individual contributions of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven to the evolution of Sonata Form, a natural question arises: how does this form manifest itself in actual compositions? Examining specific musical examples allows us to move beyond theoretical definitions and appreciate the practical application of Sonata Form in some of the most celebrated works of the Classical and Romantic periods.

Sonata Form, far from being a rigid constraint, proved to be a remarkably fertile ground for musical innovation. Its impact resonates far beyond the Classical Era, shaping subsequent musical forms and influencing generations of composers. Its fingerprints can be traced in various musical styles, testaments to its foundational role in Western music.

The Ripple Effect: Sonata Form’s Transformation into Other Forms

The principles of Sonata Form didn’t simply vanish with the close of the Classical period. Instead, they were adapted, expanded, and reimagined, giving rise to new musical structures.

The Romantic era saw the emergence of forms like the symphonic poem and the concert overture, which often incorporated elements of Sonata Form within a more programmatic and narrative framework. Composers like Liszt and Berlioz used the basic principles of thematic development and recapitulation to tell stories through music.

Even in genres further removed from the symphony and sonata, the influence of Sonata Form can be discerned. Think of the aria structure in opera, or the larger sectional designs found in many extended instrumental works. The concept of contrasting themes, their development, and eventual resolution remains a powerful organizational tool.

Composers Embracing and Evolving Sonata Form

Countless composers after Beethoven engaged with Sonata Form, sometimes adhering closely to its conventions and other times pushing its boundaries.

Schubert, for instance, retained the fundamental structure but imbued it with his own lyrical and melancholic voice. Brahms demonstrated a deep understanding of the form, often using it as a framework for his complex and richly textured musical language.

Later composers, like Mahler and Shostakovich, stretched the boundaries of Sonata Form even further, incorporating elements of dissonance and fragmentation to reflect the anxieties and complexities of the modern world. They weren’t merely repeating the past; they were actively reinterpreting and reimagining the form for their own expressive purposes.

Sonata Form: A Cornerstone of Music Education

Beyond its influence on composition, Sonata Form plays a vital role in music education. The study of Sonata Form provides students with a framework for understanding musical structure, harmony, and thematic development.

Analyzing works in Sonata Form hones critical listening skills, enabling students to identify key thematic areas, understand harmonic relationships, and appreciate the composer’s overall design. It’s a lens through which students can deconstruct and understand complex musical narratives.

Moreover, the understanding of Sonata Form is crucial for music analysis. Whether analyzing a Haydn symphony or a Beethoven string quartet, a grasp of Sonata Form provides essential tools for unraveling the musical logic and appreciating the composer’s artistic choices.

Continued Relevance in Music Analysis

Even today, Sonata Form remains a relevant concept for music scholars and analysts. While contemporary music may often stray far from traditional forms, understanding the historical context and the underlying principles of Sonata Form can shed light on the composer’s intentions and the work’s place within the broader musical landscape.

By understanding Sonata Form, listeners and music lovers can enjoy a more informed and enriching experience. Appreciating the form’s intricacies unlocks a deeper understanding of the music’s architecture and the composer’s creative process.

FAQs About Classical Sonata Form

Here are some frequently asked questions to help you better understand the complexities of classical sonata form.

What are the three main sections of classical sonata form?

The three main sections are the exposition, development, and recapitulation. In the exposition, themes are introduced. The development section explores and transforms these themes, and the recapitulation restates them in a modified form.

What typically happens in the development section of classical sonata form?

The development section takes the themes presented in the exposition and fragments, alters, and combines them in new ways. This section often features harmonic instability and a heightened sense of drama, leading back to the recapitulation.

How does the recapitulation differ from the exposition in classical sonata form?

The recapitulation is similar to the exposition but with key differences. Most significantly, the second theme group, which was originally presented in a different key in the exposition, is now presented in the tonic key, providing a sense of resolution. This resolution is crucial to the form of classical sonata form.

Is classical sonata form a structure only found in sonatas?

No. While named after the sonata, this structure is commonly used as the first movement form in symphonies, concertos, string quartets, and other multi-movement works from the Classical period and beyond. It’s a fundamental organizational principle.

So, there you have it! Hopefully, this deep dive into classical sonata form has been helpful. Now go forth, listen, analyze, and maybe even compose something amazing yourself! Good luck!